History: The Glory Years

Design & delivery

Upon her delivery to the United States Lines, the SS United States was most graceful, modern, powerful and sleek vessel in the world. With her two oversize red, white, and blue funnels, she projected a powerful and romantic image of maritime travel, one that recalled the first great record-breaking liners of the twentieth century. Inside, she was completely fireproof. Her designer William Francis Gibbs’ passion for secrecy, it turned out, was outdone by his utter determination to minimize the threat of fire on board. Except for the grand pianos (at the insistence of the Steinway company) and the butcher’s blocks (at the insistence of the catering department), no wood was permitted in any of the ship’s public rooms, accommodations, or crew quarters. Even the fabric and textiles were specially treated to be non-flammable.

Designing attractive interiors around these strict parameters fell to Dorothy Marckwald, of the New York firm Smyth, Urquhart & Marckwald. The firm, and Ms. Marckwald in particular, had been working on Gibbs & Cox ships for decades. The ship’s 23 public rooms, 395 staterooms, and 14 first-class suites were as beautiful as they were fireproof. The emphasis was on color: Reds, blues, greens, and golds (“muddy colors” were avoided) contrasted pleasantly with oyster white walls and deep black linoleum flooring in the passageways. Artwork tended to be of glass or other spun fibers, all with patriotic themes: the first-class dining room contained sculptures representing the four freedoms, while the Observation Lounge contained murals of ocean currents and depictions of constellations. To ensure fire safety, Gibbs had an entire mock-up cabin put together at the National Bureau of Standards’ test facility, replete with Ms. Marckwald’s un-flammable furniture, and set it alight. All the “passenger effects” such as clothes, paper, perfume, and luggage were incinerated, but the cabin fittings, though scorched, were un-touched right down to the curtains.

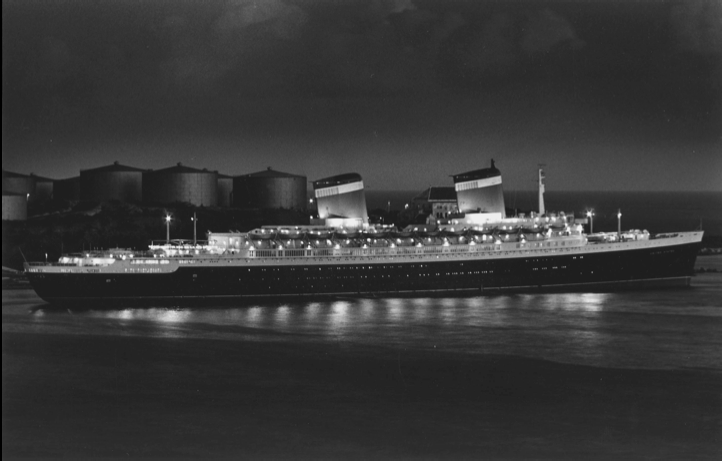

The SS United States in 1966 (Image courtesy of Nick Landiak)

The SS United States at the time of her launch, 1951

The first class ballroom is an example of the ship’s gorgeous mid-century interiors

The SS United States returns triumphantly from her maiden voyage (Image courtesy of Ronald Jensh)

The SS United States traveling at excess of 38 knots — over 44 miles per hour — on her sea trial (Image courtesy of Charles Anderson)

Blue Riband

Advance publicity for the SS United States had primed the American public for a record-breaking vessel. Secrecy was tight during the builder’s trials in June of 1952, but it was later learned that the vessel exceeded 38 knots, or 44 miles per hour. She traveled 20 knots in reverse. On July 3rd, 1952, the SS United States set forth on her much-anticipated maiden voyage, timed to coincide with the national Forth of July celebrations. Her commander, Commodore Harry Manning—a celebrity in his own right, who had been a co-pilot of Amelia Earhart—carefully avoided any promises of a record-breaking run, especially when the ship encountered a fog bank during the first day out. Once clear of the hazard, Commodore Manning, with typical bravado, ordered the ship’s engines to be increased to full power. The ship’s speed, combined with the gale force winds and heavy seas, created on-deck conditions that kept most passengers inside—or at least in the enclosed promenades. So strong was the wind speed that the adventurous few who did venture out onto the open decks likened facing forward to being punched in the face. Miraculously, the dreaded vibration expected on high-speed liners was virtually absent, even when the ship attained her highest-ever service speed of 36 knots.

America’s Flagship

The American public enthusiastically embraced the SS United States, which became known as “America’s Flagship.” Throughout the 1950s, people from around the world booked accommodation on the world’s fastest ship. Familiar names of the day, including Bob Hope, Princess Grace of Monaco, Salvadore Dali, Rita Hayworth, Harry Truman, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and Duke Ellington headlined the ship’s passenger lists. For those far inland or disinclined to travel, the United States came to them through news reports and even the cinema: the ship became a ocean-going movie set for feature films such as Walt Disney’s Bon Voyage!, Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, and Munster, Go Home!

Even after the introduction of the commercial jet liner in 1958, the ship operated at capacity during the summer high season, but as the 1960s dawned, financial trouble loomed on the horizon. The United States Lines frequently endured both labor disputes and annual wrangling with the federal government over operating subsidies. The industry itself was subjected to a rapid shift in the way people chose to travel: what air travel lacked in comfort it made up for in speed and fuel economy in an era when oil costs were beginning to skyrocket.

The SS United States in 1964 (Image courtesy of Charles Anderson)

John Wayne and Commodore John Anderson, captain of the SS United States, on deck (Image courtesy of Charles Anderson)

The 1960s proved to be a decade of loss for the United States, symbolically as well as financially. She lost her original running mate in 1964, when the America was sold to foreign interests. Four years later, her main competitors, the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth were gone as well. Although a new generation of liners, particularly the France and Cunard’s Queen Elizabeth 2 were introduced, they both spent a good part of the year on cruise duty, a role for which the United States was ill-equipped. The biggest blow came in 1967, with the death of William Francis Gibbs. His favorite ship, on which he had labored for nearly half his life, only sailed for another two years. In November of 1969, while undergoing her annual overhaul at Newport News, she was abruptly and permanently withdrawn from service.

PREVIOUS: Design & Launch | NEXT: Retirement